In this cross-posting from the AW360 site Alex Hayes asks why we’re so obsessed with giving everyone so much choice?

Every now and then you come across a new word (or in this case acronym) that captures a feeling you’ve had that you haven’t been able to put your finger on. For me, it’s FOBO.

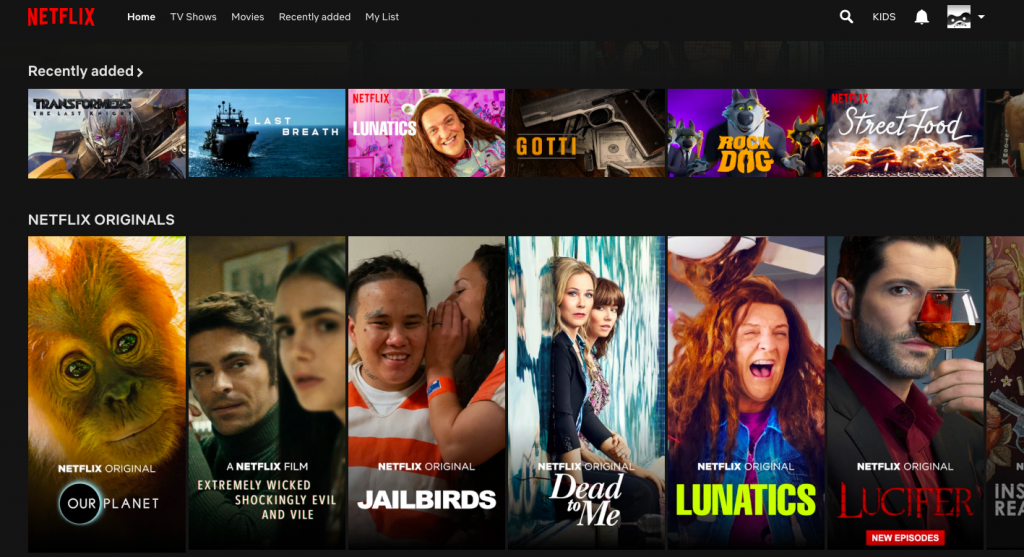

For those (like me apparently) who’ve been living under a rock since the middle of 2018, FOBO is fear of better options. Defined simply, it’s that creeping feeling you get when you’re surfing for something to watch on your streaming service of choice, find something interesting, but keep scrolling in case there’s something better out there.

I’m going to hazard a guess this is something we all recognise in some form – the choice paralysis we now face in everyday life, from the coffee counter to our entertainment options. How often have you opened Spotify and then sat there trying to figure out what you actually want to listen to?

It’s not a new thing – apparently it was coined in 2003, but it’s exacerbated by our ubiquitous access to information via our mobile devices.

FOBO can soon turn into FODA – fear of doing anything. Consequently, it’s something every marketer and media company should be thinking about when running the rule over their products and services.

And the fact that I heard the phrase for the first time at an industry conference – Advertising Week Europe – suggests to me it’s something which is starting to creep into the plans of the more forward-thinking out there.

It was certainly a topic of conversation on a panel of TV industry executives – keen to point out that streaming services, whilst offering choice, also created a feeling of isolation in the viewing experience, because everyone is at a different stage in their binge viewing journeys.

To a point they are right. Watercooler moments are still mainly the domain of the linear TV networks because of the fact the shows now are mainly appointment to view reality or sports-based, and the size of the audience they can attract. As the panelists alluded to, there’s still a huge amount of social credibility in certain circles that comes from keeping up with the very latest episodes of your favourite reality shows. And they are the talking points that fill column inches across media outlets the next day as well.

With the final season of Game of Thrones about to kick off, I anticipate we’ll see a global demonstration of this – and everyone will soon know whether it’s living up to expectations or not.

In a way the binary nature of broadcast, the appointment to view factor, is becoming a unique selling point for the medium. It’ll be interesting to see if this spawns more reality hits, with scripted drama becoming the domain of Netflix et al.

If that is the case, how will we connect with other people watching those shows at the same pace as us? Sure, there may be a couple of people in the office, but there’s also huge potential for social platforms to become a connective tissue for global communities of obsessives of the Umbrella Academy, Marie Kondo et al.

Social TV watching is in its infancy, where people are searching out hashtags to try and connect with like-minded people. Some TV networks have retreated from their own attempts to build their own co-viewing experiences, but I expect to see more innovation in this space from Facebook, Snapchat and Twitter sooner rather than later.

‘Learn to kill’

Also, at Advertising Week I caught the ever insightful Mark Ritson, who urged the audience to “learn to kill”. In this case he was addressing brand strategy at a company level and talking about how some pretty major companies have swung the axe on a number of their sub-brands in recent years.

The likes of P&G and Unilever have been pretty ruthless at getting rid of the brands which were less profitable and a distraction for their core businesses and have been much better off for it. We’re even seeing this trend in agency holding groups with Publicis and WPP culling and merging their own brands.

The recent demise of Aussie company Shoes of Prey, the much-vaunted online footwear vendor which allowed people to choose from dozens of options in order to create their ideal pair of shoes, is perhaps proof that we’ve hit peak choice for customers.

As founder Michael Fox wrote in his brave piece about the failed experiment: “We learnt the hard way that mass market customers don’t want to create, they want to be inspired and shown what to wear.”

Less, it seems, is more.

Which is why as a FOBO-suffering consumer I’m ready to get on board with more personalisation from my favourite companies. Too much choice is not necessarily a good thing.